I fell in love with fishing at 13 in 1952, when my artist mother, Stella Waitzkin, handed me a copy of Life magazine featuring Ernest Hemingway’s Old Man and the Sea. Before I was halfway through that genius novel, I knew I wanted to spend stretches of my life hunting the ocean for giant game fish. But also, while witnessing the death struggle between a larger-than-life blue marlin and an old man, I became intoxicated by the rhythm of Hemingway’s short sentences, and some strange fusion took place deep inside me — great writing and fishing became bonded.

That same year, I began struggling to write little stories, which my mother scribbled on in India ink, offering lush, near-illegible phrases and insights, and I got my first boat and began fishing for eels in Long Island Sound. Whenever I took off on one of these afternoon fishing adventures with one of my buddies, or occasionally with my salesman dad — whom my mother abhorred — Stella made a distasteful face to say, “Fishing? Why fishing, Fred? Fishing is so banal.”

“Untitled” face in resin

Meanwhile, Mother spent her days painting dark canvases in her studio, usually beginning with recognizable forms and faces that devolved into storms of passion and madness. But in one large abstract canvas, a red devil emerged from the chaos. “Who is that?” I asked, pointing to the Satan. “It’s your father,” she said, walking away without another word. My salesman father, whom I worshiped.

For Stella, anything even vaguely normal — salesmanship, fishing, baseball, religion — was pitifully banal or worse.

Over the decades of our stormy love, it probably never occurred to Stella that she’d initiated my life as a fisherman; if it had, she would have brushed it aside as trivial. My mom operated in a world of near inscrutable paradox. The discrete elements of life and art never interested her so much as the fusion that might take place when contrary elements were introduced to one another, like a meeting of the most unlikely lovers. That’s when life, when ART excited her. I recall standing with her on a bluff on the island of Bimini in the Bahamas, looking out at the gorgeous Gulf Stream. I was dreaming of marlin. “That’s art,” she said to me, pointing at a fetid pile of garbage, a broken rusting car, rotting conch shells, old cartons, that had been heaped on the beach in front of the cobalt blue water. I didn’t get it. Garbage? Art? She turned away from me, shaking her head and repeating, “That’s art,” meaning the sky, the blue deep water, the broken car and conch shells in relation to the sea — juxtaposition. I couldn’t see it then. It took me years to see it.

“Faces, in resin,” detail

Back in those Great Neck days, Mother blasted the jazz of Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane and Thelonious Monk through the rooms of our house. This bedlam she called music drove me crazy. But she laughed at my taste, and turned up the sound until the walls were shaking. “Someday you’ll get it,” she offered. These smug remarks from Stella infuriated me, along with her abstractions, which my dad despised. But Stella was right. By the time I was 18 years old, I was in love with Monk, Coltrane, and many other progressive jazz greats.

When I was a boy growing up in Great Neck, and very much in the sway of my lighting salesman father, Stella was taking the train into the city to study painting with the renowned abstract painter and teacher, Hans Hofmann. One might imagine Stella would have taken the guidance of perhaps the greatest teacher of modern art as gospel, but apparently not. Hofmann admired her roiling textures and dark soul, but repeatedly, when a recognizable image would appear at the edge of her abstraction, the great master would exclaim, “Vas ist Das?” For him, Stella was making a blunder, ruining the purity of a vision. But Stella stifled a laugh at his critique and went her own way, even with the great Hofmann. The paradox of marlin and poetry, the pristine ocean and garbage, abstraction with traces of realism, yin and yang, intrigued her throughout her personal and artistic life.

After her divorce from Abe, Stella moved into New York City, quickly forging personal relationships with some of the greatest American painters, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Malcolm Morley, Larry Rivers, Louise Nevelson among others. One evening she invited De Kooning for dinner. He came with drips and smears of dried paint on his pants. Observing the immortal painter through my father’s eyes, I decided De Kooning was a loser, a bum.

“Cherub”

By the ’60s Mother was doing more sculpture than painting, sometimes melting glass into unusual forms in a kiln, but soon discovering a passion for casting painterly books from polyester resin, books without words. Occasionally she showed her work in galleries, but often she spurned the politics of the art world and offended admirers, gallery owners, and art critics. Several times Mother had been offered solo exhibitions in galleries, and she would comment acidly of the director, “He’s a bullshit artist. What is he trying to get from me?” I recall one time she was scheduled to have a one-man show at the prestigious Lee Witkin Gallery on West Broadway. This was a huge opportunity for Stella — surely her exhibition would receive notices in all of the top magazines and newspapers. But two weeks before the opening, she called an incredulous Witkin to tell him that the opening date for the show was not advantageous to her in terms of numerology. She demanded he reschedule. Witkin was enraged, and never spoke with her again. But Stella didn’t care. She believed Lee Witkin was trying to take advantage of her in some dark manner.

Making art meant the world to my mom. But making it in the art world meant very little.

Later on, Mother bought a house on Music Street on Martha’s Vineyard. It had uncanny architectural twists and turns, mysterious stairways, interior nooks and secret crannies, like an offbeat oceangoing yacht. Over the years Mother filled her Music Street house with art and rebuke, and also with the jazz that she loved. In front of her door there was a mat with the words “Go Away.” Often Stella didn’t want to see anyone, including me. By then Stella was full-time making sculptures of books without words from polyester resin. She worked long hours, and often brought her sculptures indoors and placed them at the foot of her bed, so that when she woke in the morning she could see them with fresh eyes. The fumes from her resin sculptures were toxic, but she didn’t care. For her, art had become everything she cared about in life.

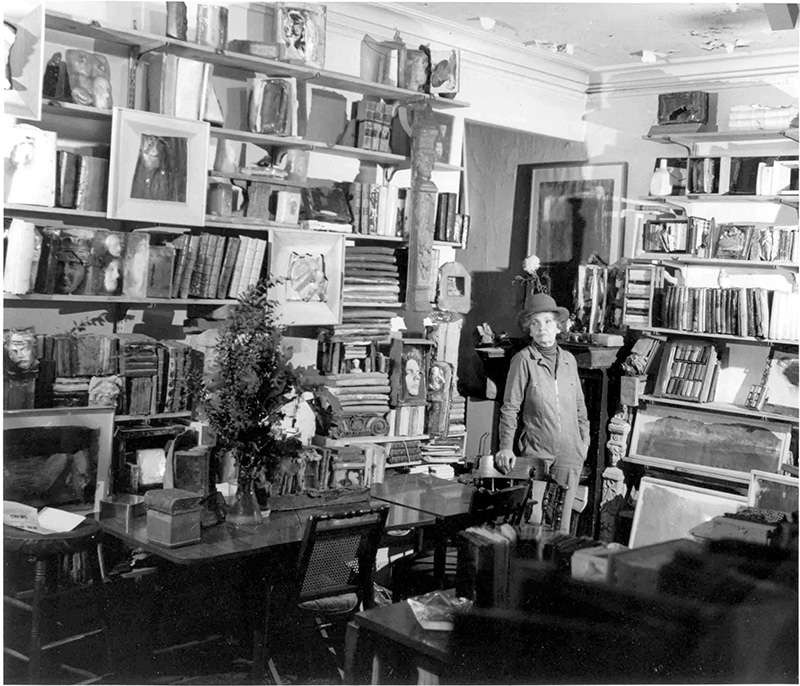

In the fall I came to the Island for two or three weeks, staying in a Chilmark house owned by my wife’s parents. I was usually working on a magazine article, but mainly I came to visit my mother. In the evening I’d come by the Music Street house for dinner, and usually when she heard my knock on the door she screamed at me to go away. She was mostly living as a hermit then, living with jazz and the smells of damp resin mixing with the aroma of beef stew or chicken soup simmering on the stove. “Go away, Freddy,” she shrieked, but I’d always force myself into her kitchen, which was crammed with art and found objects. Her entire place was a bedlam of sculpture and old books and wood, garbage, anything that she might make into art. Stella put everything imaginable inside her books without words, religious icons, baby shoes, faces of animals. She once embedded a dead bird in one of her sculptures. I’d edge myself through the art and junk to where she was standing beside the stove, give her a big hug. While she pushed me away, I kissed her chubby cheeks until she began to relax, soften and giggle … Loving Stella was always a battle.

Fred and Stella Waitzken —Lynn Christoffers

After her delicious dinner, I might show her an article of mine that had just appeared in the New York Times Magazine. She’d look vaguely interested, but was mostly dismissive. Stella shook her head to say, This isn’t the real writing, Fred. When are you going to do the real writing? Journalism meant little to Stella. Fiction and poetry were what really counted, if you were a serious writer.

Stella’s rejections hurt, to be sure, often sent me reeling, but she taught me so much. Stella taught me about color and juxtaposition, uncanny juxtaposition, to search for the loving elements in an essentially evil protagonist, or to find evil predisposition in an admirable fellow — that’s when a story becomes interesting. Stella was derisive about saints, and curious about sinners. She taught me to reach very high, to do better than I could even imagine … Sadly, Stella never lived to see much of my best work, the novels she’d been pushing me to write.

During the last year of her life, the Music Street house was so crammed with art and garbage that it was near impossible to walk through the rooms. Stella counseled me sternly that when she passed she wanted me to pile her sculptures and paintings into my fishing boat, the Ebb Tide, take the art out to sea, and throw it over the side — throw her life’s work into the fishing waters that I loved. She ordered me to do this many times. This would be the ultimate irony, the pièce de résistance of a paradoxical life vision.

But I didn’t listen.

“Forty Books,” detail

At the time of her death in 2003, Stella Waitzkin was admired by artists who knew her work, but was certainly not a prominent figure in the art world. In the ensuing 16 years, Charles Russell, a dedicated admirer of Stella and an accomplished art writer; Lynn Christoffers, our curator; and I operated an art trust with the sole mandate to help Stella’s art gain the exposure it deserved. The trust has been more successful than we could reasonably have imagined.

Since her death, Mom’s work has been acquired and periodically exhibited by 75 public museums across the country. Her work is in the collections of some of the great art museums in the world, including MOMA, the Jewish Museum, the Smithsonian, and the National Gallery, where her sculpture is presently being exhibited. The John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wis., has hundreds of individual works that they periodically exhibit in a very large installation space mirroring Mom’s living room in the Chelsea Hotel, where she lived in New York for many years. On Martha’s Vineyard, Stella’s work has been exhibited in a retrospective exhibition at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum, and has been shown many times at Tanya Augustinos’s marvelous A Gallery. This summer Stella’s work will be featured in an exhibition in the Janco Dada Museum in Ein Hod, Israel.

Sixteen years ago my brilliant, difficult, iconoclast mother ordered me to dump her life’s work into the sea. Would she be pleased that I hadn’t done it? Would she be pleased with her considerable posthumous success?

I’m really not sure.

Fred Waitzkin is a writer best known for the book Searching for Bobby Fischer. He lives seasonally on Music Street.

Leave a reply