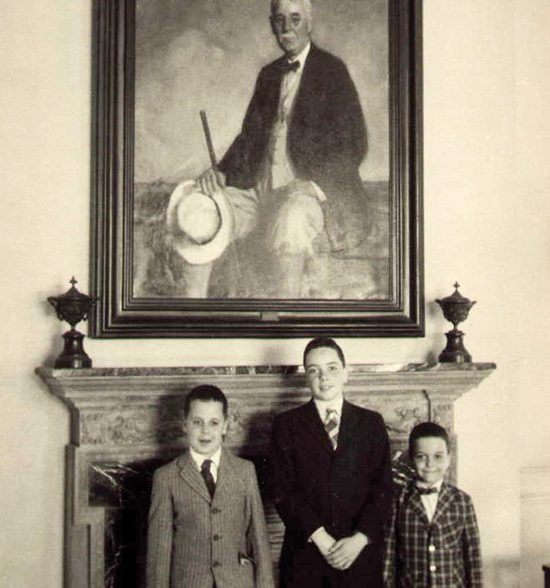

David Stanwood, right, at age seven, in front of a painting of his great grandpa Snare, in Havana.

How I made connections over 60 years of going to Cuba.

My trips back to Cuba keep completing circles for me, circles of human connections around the things that most matter to me in the world.

So many circles with me and Cuba involving sailing, piano tuning, photography, and a painting of my great-grandfather that once hung in the country club he built, before the revolution. I wish I could tell you all of my Cuba stories, but I only have room for two. I’ll start with the painting of Great-Grandpa Snare.

In 1958 I was 7 years old. We were in Florida on vacation. My father decided we would fly to Havana for lunch. He wanted to visit his grandfather’s country club one last time before Castro took over. My great-grandpa had died in 1946, but his driver was still there, and met us at the airport in a big old black Cadillac. We drove to the country club, and my picture was taken alongside my two older brothers in front of a large portrait of my great-grandfather that hung over a fireplace, with brass urns on the mantel. Then we headed to downtown Havana for lunch. We pulled up in front of a restaurant, and I got out of the car onto the sidewalk. Two young boys my own age ran up to me, begging in tattered clothes with hands reaching out. This was shocking to me. Then I turned and saw trucks full of soldiers passing by the square and a tank moving in the distance. We walked straight into the restaurant, with two armed government soldiers holding machine guns on either side of the front door. For 40 years that’s the last I remembered of Cuba.

Back in the 1970s I used to stop into the Steinway salerooms at M. Steinert and Sons by Boston Common to chat with Paul Murphy Jr. about sailing, and I would sample the pianos.

One year I asked him, “How does one learn to tune pianos?” Paul said, “Go up to the North End. The North Bennet Street School is the best in the world for piano tuning.” I walked up to the school, and was amazed to discover the world of piano technology. From 1977 to 1979 I attended the North Bennet Street School, and learned how to tune and restore pianos. Two years after graduating, I moved to Martha’s Vineyard, settled down with my wife Eleanor, and we raised our children Abigail and John. In summer I was busy tuning Island pianos, and Eleanor sheared Island sheep. In winter I restored vintage pianos, and Eleanor made wool felt in our shop on Lambert’s Cove Road. These quiet, distraction-free winters allowed me time and mind space to begin realizing my visions of inventing improvements for pianos. My pioneering work has taken me across North America, Europe, and even as far as New Zealand and beyond, teaching and educating piano technicians, and improving pianos.

In 1996 I was teaching at the annual Institute of the Piano Technicians Guild, which was held that year in Orlando, Fla. While in the exhibit hall, I came across the “Send a Piana to Havana” booth in the exhibit hall. It was all about this fellow named Benjamin Truehaft, who was bringing pianos and piano tuners to Cuba, where the pianos were in dire need of help. Ben had gone to Cuba with some piano-tuning friends to tune pianos and have some adventure. Upon his return a friend told him, “Don’t you know it’s illegal to go to Cuba? There’s an 800 number for reporting people like you!” Ben didn’t see any reason why he shouldn’t be able to go to Cuba to tune pianos, so he called the 800 number to report himself. He got no response. A little research revealed that as far as he could tell, it was not illegal to go to Cuba, but according to the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917, it was illegal to spend money in Cuba.

On his next visit to Cuba, he bought a cup of coffee, and asked for a receipt. Ben sent a letter to the U.S. State Department claiming he was turning himself in for violation of the act, and stapled the receipt to the letter as proof. He got a quick response and threat of a large fine. He complained, and the fine was raised even higher. He then asked for a hearing, and got no response. After sufficient pestering, he finally got a response from the government, which said words to the effect of “We’ve never had a hearing of this sort. We don’t want to deal with you. We’re sending you to another branch of the State Department to deal with this matter.” I read the letter, referring him to the Department of Missiles and Nuclear Warheads. I imagined them thinking ballistically: “Send a piano to Havana? No problem!”

So by this route, Ben got State Department permission to ship pianos and supplies, along with a troop of piano tuners, to Cuba. After hearing this amazing story I told Ben that my great-grandfather had had an engineering company in Cuba that built infrastructure, including the National Baseball Stadium, factories, schools, bridges, docks, the Havana Train Station, and the runways at Guantánamo. He was also twice senior golf champion of the U.S., and captain of the Senior Golf Team. He built the Havana Country Club. “We always figured they tore down the club as a bastion of capitalism,” I told him.

Ben’s jaw dropped. “David, they turned the country club into the highest institute of the arts in Cuba. That’s where we work on the pianos! You have to come to Cuba!”

So in January of 1998, Eleanor and I packed up and headed to Cuba as part of a brigade of piano tuners on a mission of mercy. After days of delays waiting in Cancún, we were finally allowed to fly to Havana. This was just before the pope was due to visit; we heard the delay was because U.S. citizens were being restricted from entering the country out of concern that U.S. agents might try to assassinate the pope and blame Cuba.

The morning after our arrival we walked onto the grounds of the Old Country Club, now called the Instituto Superior de Arte. As we approached the clubhouse, I had a feeling of déjà vu. We entered the building and they unlocked two doors to a “special room.” We entered and formed a circle in front of the fireplace in preparation for the formal reception of our group. This was the fireplace I had posed for a photograph in front of 40 years ago. The brass urns were still there, but the large portrait of my great-grandfather was missing. I had with me the framed picture taken of me and my brothers in 1958. With deep emotion I placed it on the mantle. The Cubans sensed my emotion and gathered around me with concern. They couldn’t speak English, and I managed to point at the picture and say “Mio, siete años.”

Then the opening ceremony began, with wonderful music. After dinner we went to a salsa club for some drinks with folks from the Ministry of Culture. This was a little weird, because the club was completely empty. There was a stage and long tables. These clubs hit their maximum around 1am typically. We were all sitting there together, and nothing was happening. I said to my interpreter, “Sergio. Tell them the story about my grandfather’s country club.” Sergio tensed up and refused. I admonished him, and he started talking to a ministry official named Santiago sitting next to me. I watched Santiago’s face as he listened intently to the story and as he spoke back to Sergio. Santiago said, “When I was a child my family had nothing. Not even education. After the revolution I got a full education. I went to school at the Old Country Club, and every day I would walk by the portrait above the mantle and think, ‘Who is this person? He seems like a good person. And now I meet his great-grandson.’”

It was an emotionally charged moment in which a deep connection was made between us. Afterward, Sergio apologized for not being more forthcoming. I looked at him thoughtfully and said “Sergio, are you embarrassed that your government took my great-grandfather’s company and the country club?” Sergio said, “Yes.” I said, “Not my problem. Let’s drink some rum!”

I could see the tension in his shoulders and body relax; he was so thankful to hear my words. I thought about that later, and realized that he was born after the revolution, and it made sense that he might think I was sore about it all.

During our week of work at the country club we got to know Racquel Carreras, a wood conservator who was studying the devastating effects of comején, an airborne termite that eats pianos from the inside out. Racquel told us that the portrait of my great-grandfather might have been removed sometime during the “special period.” This was the time after the Russians pulled their economic support for Cuba. Times were very tough, and there was concern that works of art might be targeted for sale on the black market. On our last day we traveled with Racquel to the National Museum of Art in downtown Havana in search of the painting. They didn’t know the whereabouts of the painting, but told us they would try to find it.

We returned to the U.S. via Miami. Many of our party were worried about getting hassled at the border, but I figured with a State Department license, why worry? The funny thing is that when we came into Miami there were two paths: “Nothing to Declare” or “Something to Declare.” Nobody was going through the declaration path, but we had Cuban cigars and a license to travel, so headed into declaration. The inspector looked eager to finally have some luggage to look through. A uniformed agent asked, What do you have to declare? I said, Cigars. He said, Where did you get them? I said, Cuba. He yelled to the agent, It’s OK, you don’t have to search his luggage! I said, What’s up? He said, If you had bought them in Mexico, then we would have to confiscate them. There was never a question about having a license to travel to Cuba. Go figure!

Eventually — about six months after our visit — Raquel located my great-grandfather’s portrait. She said it had been cut out of the frame and folded. Someone had been trying to sell it on the black market and they got caught and went to jail but, as Raquel said, “Only for a day.” The painting went to the restoration center in Havana, and languished for years because the director had no interest in restoring it. Finally, years later, a new director took interest and the painting was restored as a graduate student project. In October 2014 the story was featured in Herencia, a U.S.-published magazine devoted to preserving and promoting Cuban heritage, cultural values, and accomplishments. Racquel told us that eventually it would be returned to its place above the mantel at the Old Country Club. Eleanor and I looked forward to seeing it there someday. But first, another story, of another circle completed.

In 2013 the Harlem String Quartet had come to the Vineyard to play for the Martha’s Vineyard Chamber Music Society. The principal violinist and cofounder was Ilmar Gavilán. That first summer I took them all for a sail out of Tashmoo on our 30-foot sloop Prelude. It was an easy sail with just a little wind, inside the harbor. We got out into the Sound and the wind gave out altogether, so I anchored off Chip Chop and put up the sun tarp, and we ate comestibles and swam. Ilmar was most enamored with simply being on the water in a sailboat. As the tide started to flood, the boat hung on the anchor, and Ilmar hung off the stern in the water drifting back in the current with a rope around his foot and his arms out to the side like a cross. He was in some sort of heavenly state, like a water spirit. I learned that he was from Cuba.

The 2015 quartet came again to play on the Vineyard, and again I invited them all for another sail. All found reasons not to come except for Ilmar. We had a wonderful wind, and Ilmar spent a lot of time at the tiller sailing. He seemed to be in his element, and was overjoyed to be sailing. We had a wonderful time, and I shared my story of tuning pianos in 1998 at the Instituto Superior de Arte in Cuba, at what used to be the Old Country Club built by my great-grandfather, Frederick Snare.

In October 2016, Ilmar contacted me about working on his brother Aldo’s Steinway in Havana. Aldo is an accomplished and successful pianist and composer with an eclectic style. He wanted to use his mother’s 1918 vintage Steinway M for composition and recording. The piano had just been restrung and worked on, but he was not happy with the result. I made contact with Aldo’s manager, and we made arrangements for a trip to Cuba. I learned later that I got the referral because Ilmar felt I “was a good person.”

On a very cold Feb. 4, 2017, Eleanor and I got on a flight from Boston to Fort Lauderdale, Fla., then from there to Havana. Aldo said he would meet me us at the airport in Havana, along with someone from the Ministry of Culture to facilitate my coming into the country with parts and tools.

After we settled in, Aldo picked us up and we headed for the Edificio de Arte Cubano at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Havana for a special multimedia extravaganza by graduates from the Instituto de Superior Artes, honoring the famous and still-living Cuban painter Nelson Domínguez, who also attended the performances. We pulled up a little late, and there was a parking place right in front. We had been standing on these same steps back in 1998 with Raquel Carreras in our search for the missing painting of Frederick Snare which used to hang in the country club.

The next day we sipped our first mojitos since 1998, and they tasted just as wonderful as we remembered. Just watching the comings and goings of the people was very entertaining. At 2:30 we came to Aldo’s apartment, which takes up the 10th floor of a very narrow high-rise on the Malecón. We met Aldo and his wife Daiana, along with their little twin girls, Adriana and Andrea, who greeted each of us with a hug and a kiss on the cheek. In Cuba when people know or feel comfortable with a person, this display of affection is the custom. We immediately felt accepted and welcomed into Aldo’s family home.

We gave out gifts in a wine bag stocking, including my new CD, chocolate bars for the girls, and a beautiful ceramic bell made by our Uruguayan friend Washington Ledesma on the Vineyard. I rang the bell and said that it would bring out the good spirits. Coincidentally, at the same time, Aldo’s wife Daiana said the same thing in Spanish. We were all really amazed at that! We learned that the apartment was the family home that Aldo and Ilmar grew up in. Their father Guido, a prominent conductor and teacher, lived there as well, and on the walls were many of his paintings of sailboats. Ilmar’s love of the water and sailing connected another circle for me. Their mother Teresita, who had died years before, was a fine concert pianist and a renowned teacher who gave piano lessons to many, many Cuban musicians on the family Steinway.

Finally Aldo introduced me to the Steinway. It is in a soundproof room which he has just built as a studio. It was in pretty tough shape. I brought new parts and felts, along with my own specialized skills honed by 40 years of experience. I rolled up my sleeves and got started.

I put in many days of work on the piano to bring it into an improved condition. Then it came down to the moment when Aldo would sit down and test the result.

This is an important moment in any job of this sort. A person puts his total trust in you and commits time and resources to bring you from afar. So it came down to this moment when he would realize whether or not it was all worthwhile. I had some doubts about the piano when I first saw it, but they all faded when I heard Aldo play. What a talent! He was smiling and said, “I’ll be able to use this for recording now.” This was his goal. Eleanor came in from the sunroom and listened to Aldo’s incredible piano playing. We finally heard his amazing and sensitive, expressive talent, and felt the satisfaction of knowing that his beloved family’s Steinway was saved. Eleanor and I returned to the apartment then, and had a wonderful light dinner at the little cafeteria next door. A strange and wonderful day.

On this Friday, our last full day for this trip in Cuba, we started with listening to two recordings Aldo made on the Steinway the night before. I should say early in the morning, because he got to bed at 4 am. The first was a piece he said was inspired by my CD, “Six Meditations,” which I had given him earlier in the week. The second was a beautiful 10-minute improvisation that was a revelation of the awakened spirit of the family’s Steinway. (To hear Aldo’s recording of the first piece, click here: bit.ly/ALDO4David.) We stopped for lunch in downtown Havana. I got out onto the sidewalk and it hit me like a bolt of lightning. This was the very spot where 60 years ago I was so shocked by the beggar boys my own age!

After lunch we headed out to the Old Country Club and the director’s office, for a reunion with the restored painting of its founder, my great-grandfather Frederick Snare. The neighborhood around the country club certainly had picked up over the previous 19 years, with lots of people at cafés and on the sidewalks. We were greeted by our friend Ana, who is the librarian at the Instituto Superior de Artes (ISA) on the country club grounds. Music was floating through the air, as we had heard years before. We learned that the piano faculty had left for downtown Havana, so we heard no pianos. The special room where my great-grandfather’s portrait had hung was full of chairs stacked up, and was being used for a choir rehearsal with the little space that remained. It looked as if it would be some time before the room could be restored and the painting hung on the wall. We headed upstairs to the director’s office, and were greeted warmly.

There on the office wall was the large, restored portrait of my great-grandpa, Frederick Snare. Daniel showed us a table in the adjoining room with awards and tributes from countries around the world. The brass urns that once graced the fireplace mantel under the portrait were on either side of the table.

We went back into the rector’s office for me to sign the guestbook, which included salutations from many people around the world. I wrote that our family was honored that the country club became a great school for the arts. Fidel Castro’s writing graced the first page. We posed for the obligatory photo under the restored portrait.

Another circle that’s amazing to me: When Eleanor and I went to Cuba in 1998 and spent the week working on pianos with Ben Truehaft, the whole time there was a BBC film crew filming us. “Tuning with the Enemy” was produced as a result. In that film is a child prodigy named Aldo Lopéz Gavilán, playing on his family’s Steinway. Because of that film he was “discovered” by a benefactor, who gave him a scholarship to go to a music school in London, and that changed his whole life. Amazing that 20 years later I come back to work on that same Steinway for Aldo, who has become one of Cuba’s renowned pianists. The revolution of the arts in Cuba — as expressed in a billboard we saw on our way to the airport — is invincible.

The circles continue to turn and connect.

Leave a reply