For Irving Petlin, making art was the only option.

Curated by Tanya Augoustinos

Irving Petlin is considered by many to be one of the modern living masters. His work has been shown in renowned galleries and museums across the world. And you often think that you will be nervous, or unprepared, or even jealous in the presence of greatness. But when you are next to Irving Petlin, it is hard to feel anything other than his love. Maybe not that he necessarily loves you, even though that may be true, but rather the love he feels for his family, for his work, for this Island, and for passion and resistance of any kind.

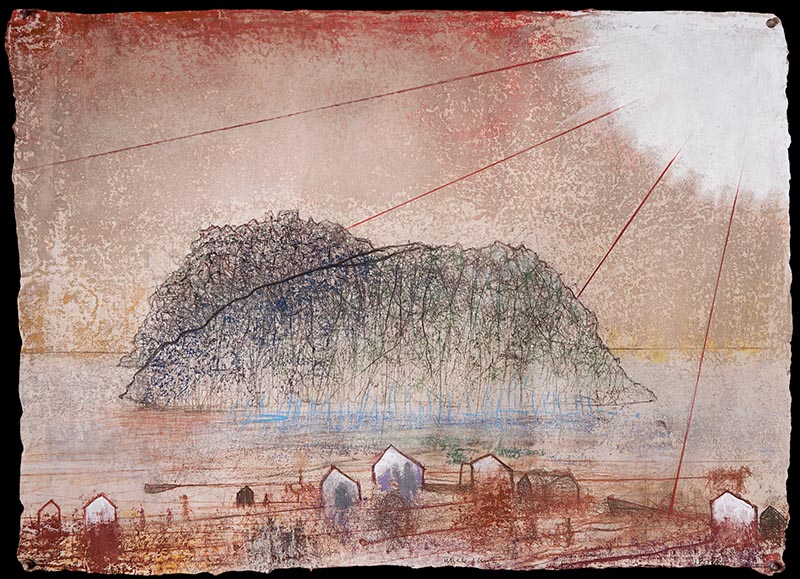

The Falls (E.W), triptych, pastel on handmade paper, 31 1/2 x 82 3/4 in.

Even though Irving has been a friend of my family’s for many years, I find it difficult to describe exactly what it is about him that gives him such an aura of love and greatness. Maybe it is in his hands, that now and again tremble with age, or with thought. Maybe it is in the broken pieces of pastels that line the wooden boxes next to the window of his studio in Chilmark. Ask him and he’ll tell you about La Maison du Pastel in Paris, the oldest pastel manufacturer in the world. Known as Roché pastels, it is the same company that made pastels for Degas; a few years back, they created a fine gold-colored pastel especially for Irving, which has been used in the recent “Aleppo” and “Immigration” series. The essence of Irving’s love is in his laugh, which is contagious, and most certainly in his art, lined in gold, yes, but also in stories told of suffering and struggle.

“There were no other options for me,” Irving says of being an artist. “I have no other skills.” His work is always tied to themes: storms, refugees, memory, the refrains of Bach’s “Art of the Fugue,” Aleppo. If you look, you will find a boat that appears, a figure that gazes down across the rooftops and water, inviting both anger and forgiveness. While creating art was the only option for Irving, there also has been no other option than to address the problems he sees in the world. “I have to deal with the real issues at hand: war, displacement, inequality,” he says. And this combination of needing to create both beautiful images and to speak to the world’s larger issues has allowed Irving to reach out of his paintings and affect those who see them — not just with their beauty, but with their message.

Irving grew up in Chicago, and left in the late 1950s to study art at Yale. In the ’60s, he moved to Paris, where he became part of a group of poets and painters — a community, he explains, of people trying to survive. “I was lucky,” he explains. “In Paris in ’61 and ’62, I had an enormous breakthrough, and began showing in an important gallery, and I felt, If I can do this here, I can do it in America.” But his return to America coincided with the birth of his two children and the Vietnam War. Irving became engaged full-time against the war, forming the Artists Protest Movement Against the War in Vietnam and, alongside a group of artists, creating the Peace Tower in West Hollywood. “People today need to understand the value of resistance,” said Irving. “You have to be willing to do whatever it takes.”

Irving and his wife Sarah raised their children in the West Village of the 1970s. “They had an interesting young life,” Irving says of his children. “A lot of artists have difficult family lives, and we had many conflicts, but we stuck together and resolved, even when it seemed impossible.” They often found themselves on a financial roller coaster, but they never assumed that Irving would do something else to support them. “It was set,” he said. “And we just kept going.”

Sometimes that meant finding a dentist who was also an art collector, willing to take a piece of art in exchange for dental care. Or another art collector willing to take a piece of art as a down payment on a home on Martha’s Vineyard. Having a house in the country was something Irving promised he would provide for his family, since he never had it growing up in Chicago.

“Martha’s Vineyard played an enormous role in our family’s happiness,” he says. “To be able to look forward to something that no one can take away from you, that was medicine to us in the wintertime.”

The family has come to the Vineyard since 1976, and Irving has always maintained a regimented day of painting in the morning and spending the afternoon at the beach. In 2014, he began showing his work at A Gallery in Oak Bluffs. “He has a very rare depth,” says gallery owner Tanya Augoustinos.

Now, at 82, Irving is still making art, but he finds joy in doing other things as well. “I’ve worked all my life,” he says. “I am going to cook for a little while.” However, there is no end to his passion for resistance, especially not now. “We must remain vigilant to the continuous assault and undermining of our democratic institutions,” says Irving. “And there can be no letup; we have to be watchful.”

To artists who cannot imagine the kind of success that Irving has had, he says, “You really have to want to do this. Because being an artist today, it’s like a roulette wheel. It’s a risk. If you want an assured life, go into IT. You can do this only if you feel it is this, or you’re going to die.”

Mathea Morais has been a regular contributor to Arts & Ideas. She teaches language arts and social studies at the Martha’s Vineyard Public Charter School, and lives with her family in Chilmark.

Tanya Augoustinos is the director and curator of A Gallery, Martha’s Vineyard. She abandoned the world of special-risks underwriting to work in the arts after exposure to theater production and art handling in New York City in the 1990s. A Gallery was founded in 2012, and focuses on contemporary art from the Vineyard and beyond.

Leave a reply