Dick Iacovello ended his U.S. Army tour of duty in Vietnam in the fall of 1963.

He would spend the next 45 years exorcising the demons of his war, finally achieving emotional and psychological freedom here on Martha’s Vineyard, using a form of art therapy devised by a national organization called Combat Papermakers.

Combat Papermakers is dedicated to relieving the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by encouraging vet PTSD sufferers to turn their wartime uniforms into paper on which they write their stories or produce visuals about their experience.

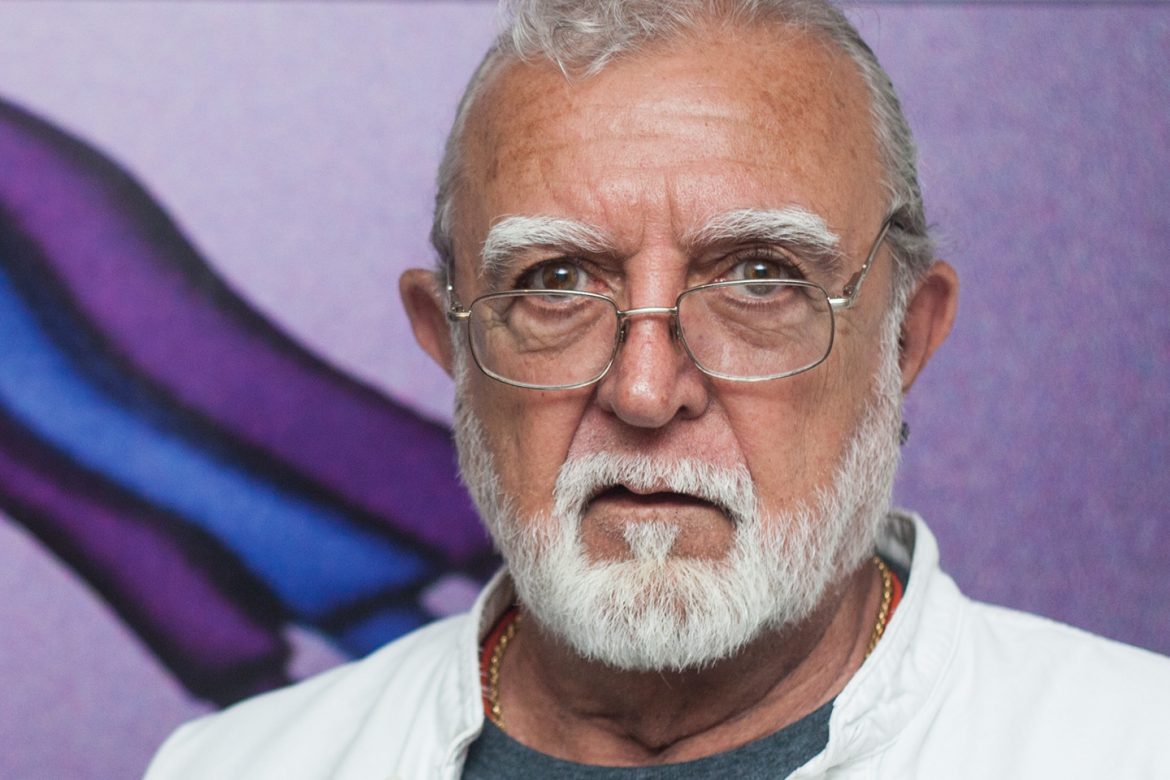

It was just what the doctor ordered for the former Quincy barber, Vietnam Army medic, and current Island artist. Mr. Iacovello, 77, recently talked with A&I about his 40-year journey to resolve war-related issues affecting his internal life.

“Memory Leak”

The day Mr. Iacovello and 16 other vets from Vietnam and Mideast conflicts gathered at Sandy Bernat’s Seastone Papers in West Tisbury began a journey of healing that has morphed into national recognition for his often stark images of war and his Vietnam experience, printed on 12 pieces of textured paper created from his field cap.

Ms. Bernat donated her studio to the papermakers that day, and recalls the experience clearly. “They were taking symbols of their experiences, and the process of shredding their uniforms, relating their stories with each other, all were part of the process of transformation,” she said recently.

“One man, a Navy man for 30 years, was sobbing,” she said. “He had to stop for a time. The releasing process was collaborative. They were looking out for their buddies as they had learned to do in the military.”

Mr. Iacovello says of the experience: “It inspired me to print more old photos that I had stored away for 45 years on the paper I had made. I was overwhelmed with the sudden release I experienced when I saw the first image from so long ago. I emailed the results to Drew Cameron and Drew Matott, the two artist papermakers who organized Combat Papermakers.

“They asked if I had more photos from that time,” Mr. Iacovello said. “That began a long friendship with them. They printed lots of my photos on the handmade paper. My images have been featured in exhibits that have toured the country, and were picked up by Viet Nam Magazine in a 2011 article titled ‘From Rags to Redemption.’ After that, I was contacted by Tara Leigh Tappert from the John W. Kluge Center’s war museum at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., and gave her permission to put them on view there.”

Earlier this spring, Mr. Iacovello was informed by a curator at the Library that his images had been accepted and are now a permanent part of their war photo collection. His notification from Ms. Tappert reads in part, “You are represented in the collection through Drew Matott’s piece — ‘What We Left Behind,’ as the image is based on your 1963 photo from Vietnam. The image and information that you sent to Katherine Blood [the Library of Congress curator] will be included in the file for this piece, which will be a part of the entire Combat Paper Project gift to the Library of Congress.”

Mr. Iacovello handles the photos of his war with assurance these days. “I have some distance from the events now. They don’t have the hold on me that they used to,” he said.

“Agent Orange”

For many Vietnam vets, the war did not end after service in Vietnam. They returned to a country opposed to the war and a military not attuned to their hidden wounds. Mr. Iacovello, who survived an unrecorded helicopter crash from enemy fire, was judged 60 percent disabled after his active service. His disability was reduced to 40 percent, and not until 1997, after several decades of appeals, was he judged to be 100 percent disabled.

“One of my jobs in remote camps was to create a safe perimeter around the base by defoliating the area,” he said. He used Agent Orange, the Army’s defoliant of choice.

Mr. Iacovello takes a “that-was-then, this-is-now” perspective. He is aware that those long-hidden photos from his past have unlocked a new future.

“For me, it was a way to release my demons, and meeting the papermakers was the way to release it. And maybe my work can help somebody else,” he said.

Leave a reply