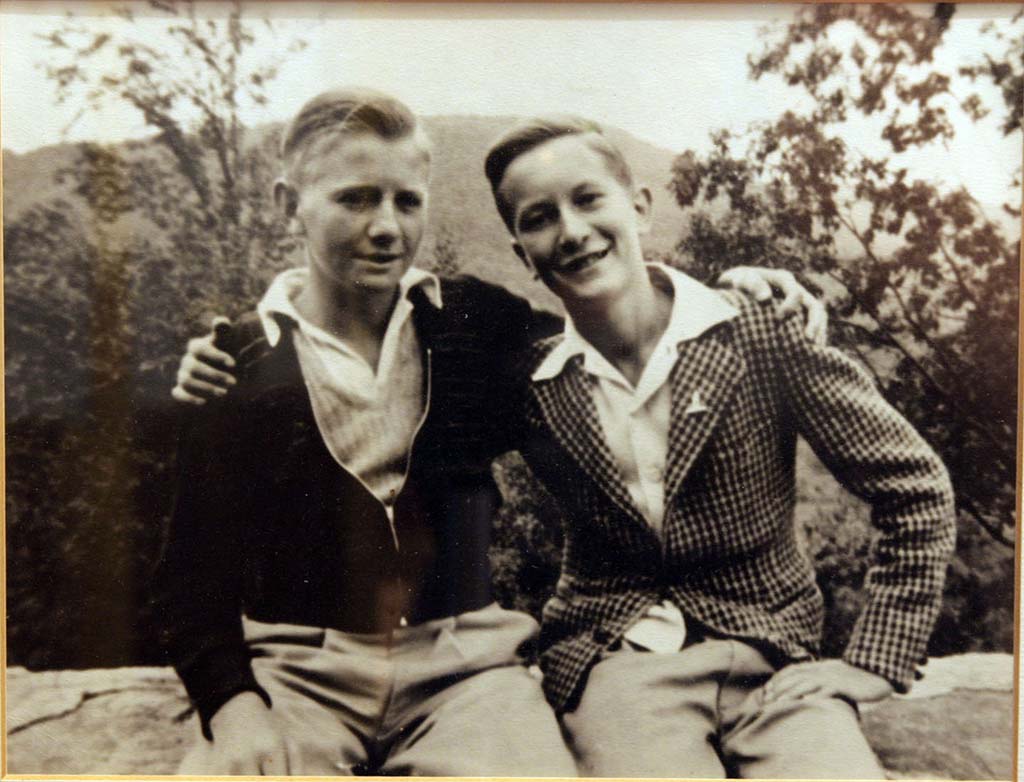

For seven or eight months during my 14th year, I kept a diary. This was in the late 1930s, when I was living in southern Virginia with my father and a male cousin a little older than I — my mother having died a year before. Because of the absence of my mother, there was considerably less discipline in the household than there ordinarily might have been, and so the diary — which I still possess — is largely a chronicle of idleness. The only interruptions to appear amid the daily inertia are incidents of moviegoing. The diary now records the fact that hardly a day went by without my cousin and me attending a film, and on weekends we often went more than once. In the summertime, when we had no school, there was a period of 10 days when we viewed a total of 16 movies. Mercifully, it must be recorded, movies were very cheap during those years at the end of the Great Depression. My critical comments in the diary were invariably laconic: “Pretty good.” “Not bad.” “Really swell movie.” I was fairly undemanding in my tastes. The purely negative remarks are almost nonexistent.

Among the several remarkable features about this orgy of moviegoing, there is one that stands out notably: Nowhere during this brief history is there even the slightest mention of my having read a book. As far as reading was concerned, I may as well have been an illiterate sharecropper in Alabama. So one might ask: How does a young boy, exposed so numbingly and monotonously to a single medium — the film — grow up to become a writer of fiction? The answer, I believe, may be less complicated than one might suppose. In the first place, I would like to think that, if my own experience forms an example, it does not mean the death of literacy or creativity if one is drenched in popular culture at an early age. This is not to argue in favor of such a witless exposure to movies as I have just described — only to say that the very young probably survive such exposure better than we imagine, and grow up to be readers and writers. More importantly, I think my experience demonstrates how, at least in the last 50 or 60 years, it has been virtually impossible for a writer of fiction to be immune to the influence of film on his work, or to fail to have movies impinge in an important way on his creative consciousness.

Yet I need to make an immediate qualification. I do not wish to argue matters of superiority in art forms. But although I cannot be entirely objective, I must say here that as admirable and as powerful a medium as the cinema is, it cannot achieve that complex synthesis of poetic, intellectual, and emotional impact that we find in the very finest novels. At their best, films are of course simply wonderful. A work like Citizen Kane or The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (by one of the greatest of directors, John Huston, who, interestingly enough, began his career as a writer) is infinitely superior, in my opinion, to most novels aspiring to the status of literature. But neither of these estimable works attains for me the aesthetic intensity of, say, William Faulkner in a book like The Sound and the Fury, or comes close to the profound beauty and moral vision of the novel that, more than any other, determined my early course as a writer: Madame Bovary.

After saying this, however, I feel obliged to confess without apology to the enormous influence the cinema has had on my own writing. Here I am not speaking of films in any large sense contributing to my philosophical understanding of things; even the films of Ingmar Bergman and Luis Buñuel, both of whom I passionately admire, fail to achieve that synthesis I mentioned before. While a fine movie has changed my perceptions for days, a great novel has altered my way of thinking for life. No, what I am speaking of is technique, style, mood — the manner in which remembered episodes in films, certain attitudes and gestures on the part of actors, little directorial tricks, even echoes of dialogue have infiltrated my work.

I am not by nature a creature of the eye (in the sense that I respond acutely to painting or pictorial representation; I vibrate instead to music), but I’m certain that the influence of films has caused my work to be intensely visual. I clearly recollect much of the composition of my first novel, Lie Down in Darkness, which I finished when I was 25. So many scenes from that book were set up in my mind as I might have set them up as a director. My authorial eye became a camera, and the page became a set or soundstage upon which my characters entered or exited and spoke their lines as if from a script. This is a dramatic technique that by no means necessarily diminishes the literary integrity of a novel; it is, as I say, a happy legacy of many years of moviegoing, and it has resonance still in my latest work, Sophie’s Choice. For example, I wrote the scene toward the end of the film where Stingo ascends the stairs in the rooming house to view the dead bodies of Sophie and Nathan with such an overpowering sense of viewing it through the eyepiece of a movie camera that when I saw the episode re-created in the film, I had a stunning sense of déjà vu, as if I myself had photographed the scene, directed it, rather than written it in a book.

Indeed, the film version of Sophie’s Choice gives me an excellent opportunity to sum up my attitudes toward the relationship between literature and the cinema. Alan Pakula’s production is, I think, a remarkably faithful adaptation of the novel, the kind of interpretation that every writer of novels ideally longs for but almost never receives. When I first saw the film it was a joy to note the smooth, almost seamless way the story unfolded in scrupulous fidelity to the way I had told it; there were no shortcuts, no distortions or evasions, and the sense of satisfaction I felt was augmented by the splendid photography, the subtle musical score, and, above all, the superb acting, especially Meryl Streep’s glorious performance, which of course is already part of film history. What then, when it was all over, was the cause of my nagging uneasiness, the sense that something was missing?

Suddenly I realized that much that had been essential to the novel had been quietly eliminated, so much that I could scarcely catalog the vanished items: the important digression on racial conflict, the philosophical meditations on Auschwitz, the intense eroticism between Sophie and Nathan, the exploration of anti-Semitism in Poland, even certain characters I had considered crucial to the novel — these were but a few of the aspects which were gone. Yet in no sense did I feel betrayed. After calm reflection I understood the necessity for the absence of these components: Many things had to go; otherwise a 10-hour film would have ensued. But more significantly, those elements which had been so carefully integrated into the novel, and which were so important both to its execution and to that sense of density and complicity which makes a novel the special organism it is, were those which most likely would have ruined the film had there been an attempt to include them.

Thus the film had to be not a visual replica of the novel — such was impossible — but a skeleton upon which was hung only the merest suggestion of the novel’s flesh. For me it illustrated more graphically than anything the necessity for not expecting a film to perform a novel’s work. The two art forms — basically so different — coexist but rarely achieve a coupling. At best, a film (like Sophie’s Choice) can take on a felicitous resemblance, as in a fine translation of a poem from a difficult language. And that is no small achievement. But even the most satisfied moviemaker will say, if he is honest, that for the true experience one must return to that oldest source — the written word — and confront the original work.

Leave a reply