The Photographic Reinventions of Sarah Mayhew

It was very difficult to accept that I could no longer do things anymore,” she says. “It was exceedingly frustrating and very hard to figure out how to make the transition, to figure out how to live my life.

When I was a child in West Tisbury, I learned how to ride and was encouraged to swim by my long-legged, beautiful blonde babysitter. Ten years my senior and a thousand times the athlete I could ever be, Sarah Mayhew introduced me to the magical world of horses, and held my hand in the surf at the Quansoo cut. About to graduate high school and go off into the world with her beau, she was the embodiment to me of all the good things to look forward to in life.

She also happened to be a photographer. Among other things, she took photos of high school away-games for the Gazette. I was aware of that, but perhaps because I was more interested in horses than in cameras, I had no idea how good she was. Or how seriously she was taken by Certain People. For example, here’s a letter she received in 1973 after a big basketball game at Boston Garden that the Vineyard lost:

“I have just received our last week’s Gazette and it gives me a chance to tell you what a wonderful job I think you did on the basketball team. I thought your pictures at the end told more of the feelings of the players and their supporters than anything I had been able to read about their disappointment, and I just wanted to express my thanks for a wonderful job. Sincerely, James Reston.”

Not a bad endorsement from one of the editors of the New York Times, and the owner of the Vineyard Gazette.

So, sure, Sarah was a photographer. But that was on the side. First and foremost, she was Horsewoman. That wasn’t just my bias; it was how she saw herself. “I was very excited to get that letter,” she says. “But at the time, my passion was horses. That overrode everything. I was obsessed. So rather than pursuing a career in photography, I did the horse thing.” After graduation, she went off to California to study at the Pacific Horse Center. Although she was still doing photography for fun, her primary energy went into athletics — training horses, riding horses, backpacking, playing tennis, swimming. When she left the Vineyard, I was still pretty young. Our families have always been close, but for about a decade, Sarah and I rarely saw each other in person. I had other babysitters and other horseback riding instructors, although Sarah remained my favorite and my greatest inspiration.

When we reconnected years later on the Vineyard, I met a very different Sarah from the athletic wonder of my youth. This new Sarah was suffering from (at the time undiagnosed) Lyme disease. When she was 26, she had gotten sick with mono-like symptoms… and never got better. She had to abandon her plans of an equestrian life, and focus on simply getting through the day. For more than thirty years now, she has had constant relapses. She has also survived neck injuries, a burst appendix, breast cancer, chronic migraines, and fibromyalgia (the latter two probably due to the Lyme).

After graduating from University of California, Davis, with a degree in landscape horticulture, she got a job in the horticultural department there for nine years, but her illness eventually eroded her ability to keep a full-time job. She went on disability. Then it got to the point where even part-time physical work was too much.

“It was very difficult to accept that I could no longer do things anymore,” she says. “It was exceedingly frustrating and very hard to figure out how to make the transition, to figure out how to live my life. It was very depressing. I went through some very difficult years trying to deal with that.” Photography had to fill the space left vacant by all she suddenly could no longer do. “I was in so much pain, and so sick, that I realized I had to do something I absolutely loved, or I wasn’t going to make it. I wasn’t going to survive, when I was in so much pain and so fatigued and exhausted.”

Between adults, ten years is not a generational difference. Sarah and I are friends and yet I’m still so aware of her as a formative figure from my childhood, that she will always loom larger than a peer. I’ve watched in admiration from the sidelines as she has shaped her new self. I’ve watched her take her talents, her needs, and her abilities and weave them together as a defense against her illness. In her late thirties, still on disability, she went for a master’s degree in studio art photography, at California State University at Sacramento, graduating in 1994. “I went out on a limb, because I knew it wasn’t going to be an easy way to make money,” she said, “but I just had to do something I could lose myself in enough to get through the day.”

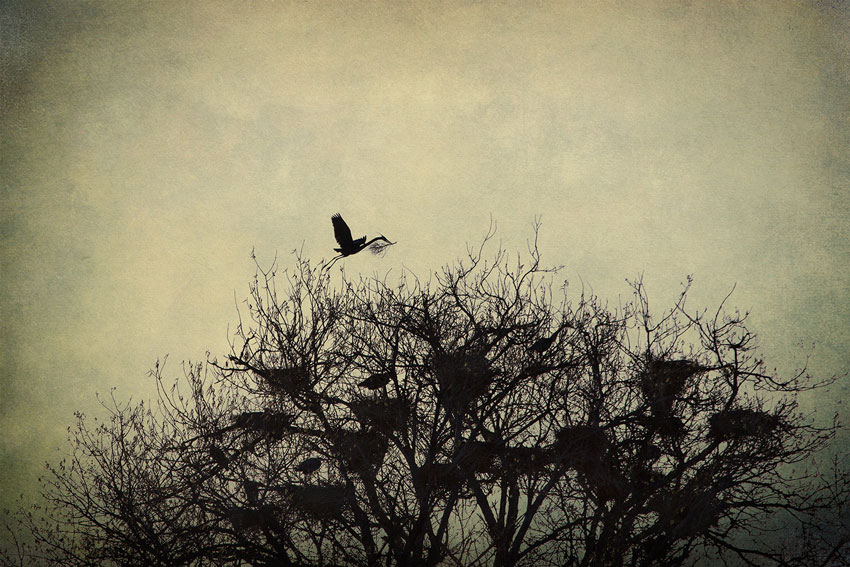

Having followed her work over the twenty years since then, I’ve seen a couple of notable themes. The obvious one, which anyone who knows her will mention instantly, is her fascination with birds. The second is a fascination with surfaces, textures, layers, and superimposed images. But most of all, Sarah to me is defined by her refusal to define herself. More than any artist I know, Sarah had resisted developing a “brand” and is constantly reinventing herself (this is also true of her ancillary creative work with fired clay). As a writer as well as a friend and fan, I’m constantly tempted to read metaphorically into all these things.

First, the birds. It seems to me that Sarah’s preoccupation with bird photography — besides the aesthetic fulfillment and sense of achievement — stems from a kind of ornithological envy. Her body is increasingly restrictive; a bird’s body is pure mobility and movement. What better antidote to physical limitation than to absorb your energy into communing with an eagle or a hummingbird?

On a less fanciful note: Sarah’s love of birds goes back to her West Tisbury childhood, when her mother Shirley, a portrait photographer and a naturalist, introduced her to a box camera and a dark room, and coached her to identify creatures and elements of nature around Look’s Pond, in their backyard. (Shirley herself wrote a book on this topic: Seasons of a Vineyard Pond: A Journal). “I got really into identifying things — birds, insects, wildflowers — but I’ve always especially just loved birds. But I didn’t get seriously into them until I could photograph them. You spend a lot of time observing them and studying them. I could go out photographing and be so absorbed in photographing that I could forget what pain I was in. It was very noticeable — I’d come home and collapse and then realize that I hadn’t been in pain all day. My illness obviously curtailed what I could do, but at least the birding distracted me enough and I loved it enough. And I was lucky to get part-time work teaching [photography], so I could make some money at it.”

Most of what I know about photography, I learned a few years ago from Sarah at 5 am on the edge of a Florida swamp full of birds. For all her debilitating pain, she had immeasurably more stamina for birding than I did. She regularly spends hours at a time almost unmoving, looking through her lens, studying her subject and taking hundreds, even thousands, of shots, adjusting aperture and shutter speed, pushing the film speed — but mostly watching, observing, following. Her patience leaves me speechless. “It’s extremely difficult,” she says, “which is what keeps me going. It’s a neverending challenge, trying to get birds in flight and so on — it’s very exciting.”

Her bird photography is extraordinary, and the range is remarkable: birds in flight or diving, fishing, hunting, flirting; birds at rest; birds up close; birds flying against the clouds or the moon. Everything about the photos is compelling: the composition, the colors, the use of light, the personality and behavior of her subjects.

For Sarah, though, that’s just the start. “Straight photography of birds . . . it’s not enough for me. The great part is being outdoors in nature and beauty, but that doesn’t really satisfy my creative urges. I want the image to have more impact, more depth. I want to take it to another level. I’ve always been disappointed that I’ve never had the patience to paint or draw, but I have a need to be creative, and straight photography doesn’t always cut it for me.” (After birding with her, I am left wondering what her definition of “patience” is.)

The other two themes of Sarah’s work — texturing and reinvention — also strike me as symbolic of how her creative work is the antidote to her illness. Who, trapped within bodily strata of discomfort, would not want to counterbalance that with added layers of attractive, aesthetic distraction? Who, living in chronic pain, would not want to reinvent themselves?

Sarah’s effects these days are enabled by Photoshop, but her tendency to play with textures and try new looks predates Photoshop by many years. Her early work was mostly arty black-and-white landscapes and still life, using a four-by-five large format. She kept playing with new forms, styles, and approaches, pushing both her own creativity and the art form itself to the limits. She loved experimenting: for example, she would lay a sheet of Mylar on a table, and then photograph the reflection of colored fabrics and objects resting on the Mylar. She also created images in which she shone an underwater flashlight through faceted crystal objects to create light patterns, which then hit the backdrop, on which she placed various objects.

Now, in the age of digital photography, she shoots textures — cement walls, fabric, wood, metal surfaces — and layers them over original photos. She layers many textures, then add colors and uses other effects that seem almost magical to anyone unfamiliar with Photoshop. “I learned Photoshop a long time ago and even taught it for a few semesters. It’s limitless what you can do in Photoshop, it’s limitless. I like the painterly look because, like I said, I don’t have the patience to paint,” she says.

Even as her physical energy is tenuous her mental and creative energy most certainly is not. She constantly works on new ideas and experiments with new looks to keep from getting bored. “I’m all over the place,” she says, “I don’t want to do just one style. I have images that look like prints, then there are ones that look more like watercolors. I love to experiment. And who knows what will trigger change?”

I eagerly await the next reinvention.

Leave a reply