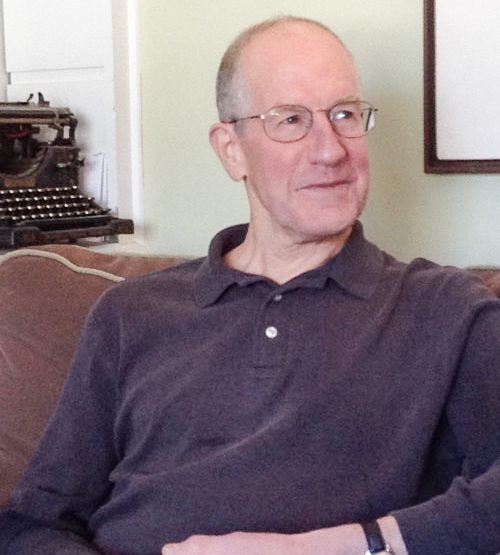

John Hough, Jr. Photograph by Laura D. Roosevelt

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, which took place beside the river of that name in Montana, on June 25, 1876, has been vivid in our collective imagination — a garish saga of the Old West. Hollywood has loved it; there have been dozens of movies about the battle, beginning in 1909 with a hectic wild-west melodrama called On the Little Bighorn; or, Custer’s Last Stand. There were five films by 1913, and at least one in every decade since then, through the 1980s. (If you want a good laugh, watch They Died with Their Boots On, 1941, with Errol Flynn as a sensitive George Armstrong Custer, who takes the field against the Indians reluctantly, calling the campaign “a dirty deal.”) More histories have been written about the Little Bighorn than about Gettysburg, Antietam, Bunker Hill, or the Alamo. I’d be surprised if there are as many histories of Agincourt, Waterloo, or D-Day as there are of Custer’s legendary sendoff. There are, incredibly, over a hundred novels.

It’s easy to see why. The story of the Little Bighorn unfolds like a morality play, down to the moment, indelible in the imagination, when Custer and those still with him knew they were going to die. Custer’s scouts had told him there were more Indians in the valley of the Little Bighorn than he could handle, but he went anyway, and his hubris resonates down the years. So do his courage, his dash, his charm. He had charisma, beyond a doubt. There are probably more photographs of him than of Lincoln.

His legacy has been controversy, from the day he died. No battle generates more arguments. Was Custer a hero, a villain, or something in between? Did he have any choice, given what he knew, but to attack the village? Should he not have divided the regiment, as he did, into three battalions, with miles of separation between them? Did his officers let him down? Did Captain Frederick Benteen, a battalion commander who was ordered by courier to “come quick,” disobey willfully, leaving Custer and his command to be massacred? Was Major Marcus Reno, the third battalion commander, drunk on the afternoon of the battle? (He was drunk that night, no question.)

Native Americans, understandably, celebrate the battle, and history these days is unfriendly to Custer. The judgment is fair enough; his assignment, eagerly undertaken, was to subjugate the Sioux and Cheyenne, kill as many as he had to, and force them into the poverty and the alien way of life of the reservations. The right and wrong of the Little Bighorn are pretty clear at this distance in time.

I was nine years old when the book came in the mail, a gift from my grandmother: Custer’s Last Stand, by Quentin Reynolds. I read it in a day and fell under the spell of the story — its wide-screen drama, its tragic inevitability, the flair of George Custer. I have the book still, its red cover faded to rose-pink, the spine bleached and peeling. Here is Custer, whose nickname was “Autie,” arriving at the end of the line: “Custer was surrounded . . . His men were twenty against a thousand. They were ten now, and finally only two. Autie Custer and his brother Tom knelt side by side, pouring lead into the screaming braves.” Thrilling stuff to a nine-year-old: Custer, in his white buckskins, the heroic victim of a bitter destiny.

I outgrew this version, of course, and the evolution of my thinking has pretty much mirrored that of white America’s, over 140 years. I began to see the Indians’ side of the story, as the country did. The broken treaties, dawn attacks on sleeping villages, the misery of life on the reservations. Later still, I viewed Custer as an adventurer and fool who deserved what he got.

But there was always the fascination, which inspired all those movies, novels, and histories. Custer on that dusty hill, his men dying around him, arrows raining down, horses screaming. We know it will end like this, but he does not as he leads his men to the river on that hot midday, pausing to divide the regiment into three battalions because he thinks the Indians might scatter and escape. He is last seen on a ridge in silhouette against the sky, standing in his stirrups and waving his Stetson in an arc above his head, urging on Major Reno, who is fighting in the valley. Shakespeare could have written this.

Nearly sixty years after Custer’s Last Stand arrived in the mail, I sat down to write my own imagining of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. My previous novel, Seen the Glory, comes to its climax at the Battle of Gettysburg, and it occurred to me that the Little Bighorn, unlike Gettysburg, changed nothing. It only postponed the inevitable. There was a meaninglessness to it, a futility, that has been lost in the celebrating, the arguing, the romance of the “last stand.” We’d all missed the point. What did men die for at the Little Bighorn? This heretical question, and its answer, are the premise of my novel.

After the battle, over time, men of various, and often murky, backgrounds emerged from obscurity to announce that they had ridden with Custer’s doomed command and survived. Their stories were usually worth a few days’ notoriety; newspapers loved them. Some were patently absurd, some faintly plausible, and all were dismissed by the experts. But I wondered: could someone have gotten away? The battlefield is vast, rugged, broken by sudden folds and brush-choked gullies. The air was thick with smoke that day. I asked historians of the battle, and it was unanimous: it could have happened. No one had any doubt.

It was what I wanted — a witness to that indelible moment, who lives to tell about it — or not to tell, if he chooses. We have the Indian accounts, of course, but the Indians couldn’t see into the hearts of those white men in that last, desperate half-hour of their lives. Native accounts of Custer’s final moments are unreliable and probably invented for the gratification of interviewers; few of the Indians knew it was Custer they were fighting, and the field was a bedlam of smoke and noise and killing. My truth, then, would be the truth — a truth no historian could know.

Custer took his brother Boston, age 27, and their 18-year-old nephew, Autie Reed, on the campaign, as a lark. The boys would experience the strenuous life on the Great Plains, and bear witness to the subjugation of Chief Sitting Bull. Two young civilians, observers who were not required to fight: history’s gift to me. I could send a boy of my own with Custer, and no one could say that couldn’t have happened. Boston and Autie were eager to go hunt the Sioux and Cheyenne, but my protagonist, Allen Winslow, is a Phillips Academy schoolboy with pacifist tendencies, who rides with the soldiers reluctantly. He rides into battle close to Custer. He sees it all, and the events of that hot June day cause him to reject any notion of a loving God.

The battlefield at Gettysburg, where Custer also fought, has the somber feel of a churchyard. It is green in spring and summer, bucolic. The gray monuments, the statues, give the place the feel of an august and stately outdoor museum. The national cemetery there is shaded, quiet, beautifully kempt. In spite of the horrors these dead saw and suffered, they are at peace now. Slavery is a memory. The Union endures.

The Indians’ victory over Custer achieved nothing in the end, and the ghosts at the Little Bighorn know no peace. They are troubled, restless, and you can feel their unsettled presence over the dry, sage-littered hills that slope down to the river. These men with Custer were terrified. Some killed themselves. Others, captured alive, died terrible deaths.

And for what? Their cries linger in the bright, dry air, and I have walked the battlefield, and I have heard them.

Leave a reply