The sentence “I don’t have an artistic bone in my body” is not one you’ll ever hear in Andrew Moore’s house. You walk into the house, in Harthaven in Oak Bluffs, and there is artwork everywhere — not just on the walls and tables and countertops, but also stacked on the floor and leaning up against the beams.

“This house is kind of like one of those urban studio complexes,” says Andrew, “with different artists working everywhere.”

This is the kind of household whose members are perhaps less likely to discuss the Big Game yesterday than they are to chew over the question of realism vs. photo-realism:

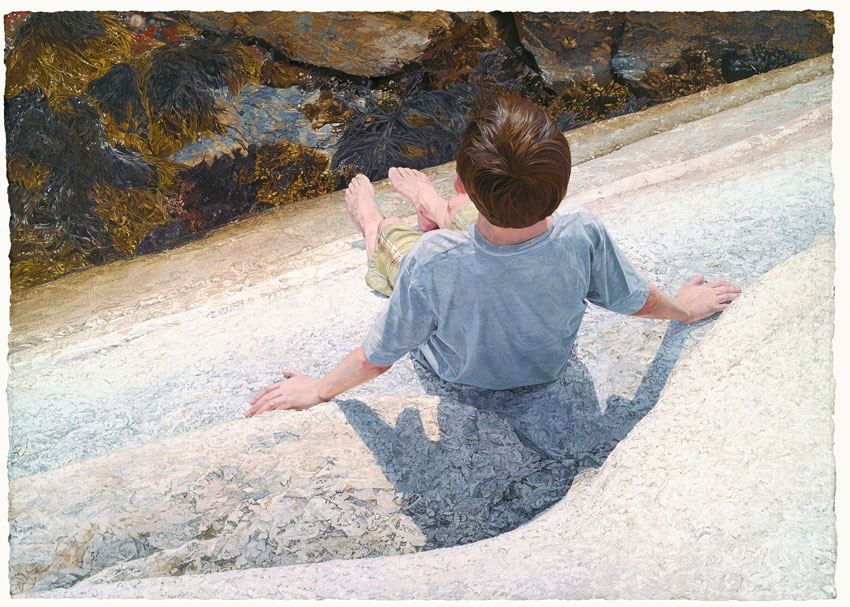

Andrew Moore: “There’s a big difference between the two. Most realists are really good fundamental drawers before they ever start painting, but photo-realists can skip that whole learning process and go right into the exercise of color matching. It’s the difference between a painting that might take months and months to do, and one that might be made in a kind of espresso production process.”

Gordon Moore: “I’m a realist. My parents’ art, and the art in our house by our other relatives, is mainly realism. Maybe it’s genetic.”

Hannah Moore: “Realism captures the wonders of the world — not just how I see it, but also how I feel about it. Sometimes I feel that I have to validate that a painting I might put on my website was done from life. I want people to know I didn’t use a photo for it. Though sometimes photos are helpful, because you can’t always expect what’s before you to sit for hours and hours without changing.”

Andrew Moore: “In realist painting, deciding what goes inside the frame is just the start. You might change the lighting, remove or add objects, recompose; there is so much humanness in the process, the decisions about the way you layer the paint, the creative maneuvering. When you do a giclée print on canvas of a photo-realist painting, there’s not much difference between the two. That’s because there’s not a lot of human soul in the actual original painting; it’s more of a technical activity.”

Heather Goff: “When I did my daily sketch project” [a drawing a day, done on her computer], “I tried printing a couple on canvas, but they lacked the texture you get from painting. They were flat. They work better as illustrations or posters.”

The Moore family — past, present, and extended — is replete with artists. Andrew himself is a painter who works in oil, egg tempera, and watercolors. His wife, Heather, is a ceramicist, painter, drawer, and a website designer. Their daughter, Hannah, currently working toward a BFA at Syracuse University, is a painter who also dabbles in jewelry-making and clothing design and sewing. Her brother, Gordon, who will graduate next year from Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School, is a talented ceramicist, painter, and drawer. Noemie Goff Pochat, Heather’s daughter, grew up doing theater and now teaches physics and calculus.

“Art has been a part of the family and of our lives since we were old enough to pick things up,” says Hannah.

Both of her parents could say the same. Andrew’s great-great-grandfather, Nelson Augustus Moore, was a painter of the Hudson River School. His father, Allen Moore, is a retired architect; his mother, Jenifer Mumford, an art teacher and painter. “When we were young,” says Andrew, “my mother would come home from teaching and go to work in her photography darkroom in the attic. And she had a bathtub where she was always making batiks. Our house was like one big art studio.”

Heather’s upbringing was similar. Her father, Clark Goff, studied architecture and later went into print-making. Her great-grandfather, Arthur Prince Spear (one of whose paintings hangs on the Moore family’s living-room wall), was an Impressionist. “Art was always the main activity in my family,” she says. “From the moment people started asking me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I knew I wanted to be an artist.”

Andrew points out that while many children enjoy art as a pastime, his upbringing showed him that art could be one’s life’s work. “Growing up and seeing my great-great-grandfather’s paintings in all our relatives’ houses,” he says, “we learned to associate art with a profession — not just as something to play with on the side.” Spending summers in Maine near Andrew Wyeth’s house reinforced this notion. “It was like having a rock star or a famous hockey player next door,” he says. “It kind of got stuck in my mind that art was real work, a really cool occupation.”

Another artist who influenced Andrew’s career path was Martha’s Vineyard painter Kib Bramhall. “Meeting him when I was a teenager was huge,” he says. “Here was a man I respected and liked, an athlete and fisherman and outdoorsman.” (Andrew is all of these things, too. His website bio states that “as a hunter, fisherman, sailor, and self-taught naturalist, the world outdoors is his source.”) The first time Andrew visited Kib Bramhall’s studio, he says, “I saw a real possibility of putting a life together doing this. If you don’t see that, it’s hard to make the leap from painting being like what you see in an art history book to actually doing it as a life venture.”

While Hannah has not yet decided precisely what she wants to do with her life, she knows that it will involve art, and that she will likely have a self-employed career. Her brother feels differently. “I love art,” says Gordon. “I’ll definitely always do it at least as a hobby, but maybe not as a career, unless it’s something like architectural engineering, where I can integrate art with other things like math and science.” Growing up with two parents who are professional artists, he is well aware of how difficult it can be for artists to make ends meet.

Andrew concurs: “It’s a pretty rugged way to make a living. Most artists — even those who are doing really well — spend much of their time in debt. It’s just part of the life.”

“If I won the lottery,” says Heather, “I’d spend half of every day painting and drawing.” In 2012, she undertook a year-long project in which, after her regular workday was done, she created a drawing every day, working on her computer with a special tablet and art software. “I realized,” she wrote on her Daily Sketches website, “. . . that I had completely misplaced one of my passions. Sometime in the past two decades, I stopped paying attention to my love of drawing.”

But Heather is aware that creativity can be found in almost any field, especially after you become proficient at the work. In the late 1990s Heather switched from full-time tile making to website design which grew largely out of a desire for more consistently creative work. She explains, “Once you learn the alphabet and can start forming words, then you can start writing poetry,” In web design, Heather notes, every project is different, hence inherently creative. On the other hand, she says with some irony, “as a potter, to make a living, you have to do mass production, and once you’ve created the initial mold for a tile, it becomes a manufacturing business.”

Gordon believes there is an artist’s mindset that a person can carry into any kind of work. Andrew agrees: “The core of art is making something from nothing, and that can be applied to any field.”

The ability to be happy working alone, Heather says, is essential to a career as an artist, and both of her children have inherited this ability. Gordon often spends hours after school in the high school’s ceramics studio, losing track of time. “After all the hours I’m in school,” he says, “this is the moment when I get to just be alone, and it’s when I find the most happiness.” Andrew echoes this sentiment, noting that when he’s working, he enjoys the sense of being entirely in the moment and not preoccupied with other issues in life. Hannah, too, often forgets how long she’s been working. “Then I start worrying about being a hermit,” she admits. “But conversely, if I’ve been in a social situation that goes longer than two days straight, I start needing to shut myself in my room for a while with my work. It’s important to find balance.”

All four Moores agree discipine is essential. When art is your job, inspiration is important, but showing up to work is even more so. “No one here is shy on routine or discipline,” says Andrew. “If you grow up in this household, you learn that the work is very rewarding, but it’s rigorous. That’s why Hannah is working so hard at school: she’s very aware of what it requires to earn a living as an artist, and she wants to get as much out of school as she can.”

No one in the Moore family has what is commonly thought of as “the artistic temperament.” That kind of temperament (which Andrew ascribes to bearded men in garrets, consumed with their vision, flinging paint at canvases with huge brushes, drinking excessively), does not mesh with the Moores’ lives as a fairly standard — albeit exceptionally creative — family. Andrew mimics the 1950’s TV dad calling to his wife, “Honey, I’m off to the studio!” Except, he points out, everyone else in the family is calling out the same thing. Because all four of them spend a great deal of time working alone, they make a point of uniting at the dinner table every evening. This is a family that hikes and fishes together, takes skiing vacations. It’s a family in which parents coach the kids’ sports teams and attend parent-teacher conferences. Indeed, Andrew notes, most artists he knows, including those in his own family, are “pretty stable, emotionally.”

Andrew points out that due to the large amounts of time artists spend working alone, with little feedback, they need to be self-assured, to take pleasure in and have confidence in the quality of their work. He worries about how much feedback young artists, Hannah and Gordon included, receive in a time when they can put images of their pieces on Facebook or their websites and immediately receive dozens of comments back. “I grew up making things in obscurity,” he says. “I developed my style in peace and quiet.” He believes that Hannah and other artists of her generation need to go underground for a while after school to find their own voices, free of the “noise” from parents, teachers, friends, and the local press.

That being said, he also believes that parents and teachers can help young artists by “giving them some practical knowledge of the underlying issues in art — form, composition, the basic fundamentals of how to draw.” In Hannah’s senior year at high school, her parents began to get more involved in discussing her work, as a way of preparing her for the critiques she would get in college. They felt that without an ability to be open to criticism, an artist might as well stay home and learn on his or her own.

“I used to just shut myself away and do my work,” says Hannah. “I didn’t want anyone’s opinion. But now I’ve realized that criticism can actually be very helpful. When I got used to having my parents critique me, I found that having anyone else do it was a lot easier. That’s good, because being stubborn during critiques is not a good quality.”

Learning from failure, Gordon adds, is also essential. He tells a story of hours spent making a mug with which he was particularly pleased, only to have it break during firing. While at first, understandably, he was disappointed, he came to understand that this was an important lesson about wall thickness in ceramics. “This will carry forth into my future work,” he says. “I’m actually glad that the mug broke now.”

* * *

The Moores’ house has changed little since they moved into it a dozen years ago. Artwork was everywhere then, and it’s only more so now. Some interior decorating projects that were unfinished then remain unfinished now. Describing the “one big art studio” house he grew up in, Andrew says, “Art took precedence over cleaning. The same is true in this house. My mother always said she didn’t have time for both.”

But despite this, despite all the rigors and challenges of living as an artist, Andrew — and everyone in his family — loves the creative life and wouldn’t trade it. “If a kid grows up in a regular house and wants to be an artist,” says Andrew, “his parents are sweating bullets. Here, we’re like, ‘What? You want to be a scientist? You’re going to business school? What’s wrong with you?!’”

Leave a reply