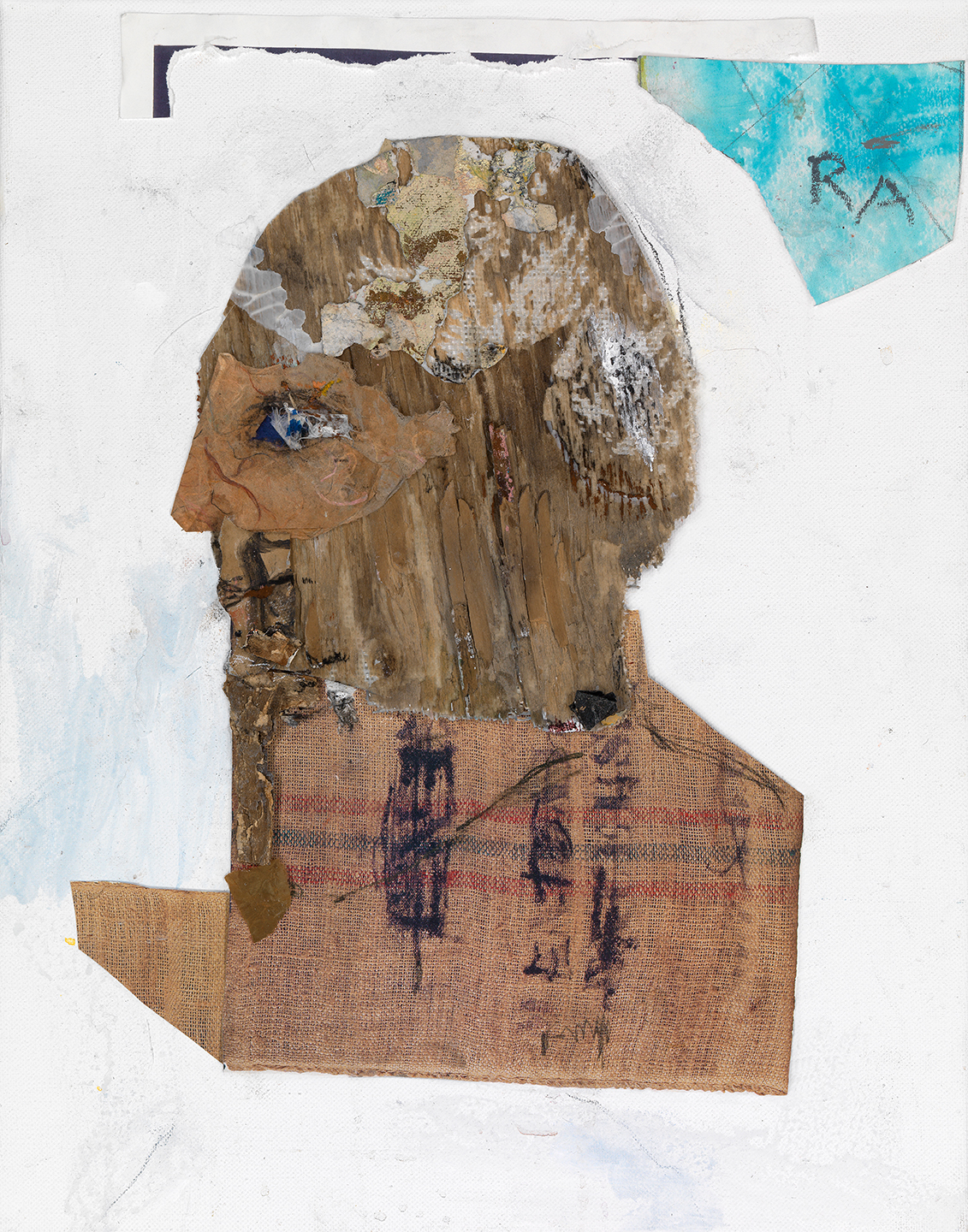

Rose Abrahmson, Lester, mixed media, 18 x 14 inches.

My mother used to make beautifully glazed and stenciled pottery bowls and baking dishes. She sculpted a two-story, pagoda-roofed toad house, and numerous frogs and toads with eccentric personalities. One toad prince stands upright on my dresser, toes spread, a clay string of beads around its neck, and a ritual headdress of my father’s old shaving brush glued to the top of its head.

The author’s mother once made elaborate toads, one of which adorns a dresser.

– Photo by Lily K. Morris

At around age 80, my mother began having mini-strokes. She had to give up driving, simple tasks became difficult, and words became increasingly hard to find — but she didn’t give up making pottery. The pots she made then reminded me of what kids first make — heavy, coiled pots and lopsided bowls in dark, uneven glazes. At the time I was still getting used to the changes in my mother (she’d startle me by asking where I was living — the same place I’d lived for thirty years), and the sight of her child-like pots made me sad. I wondered how she felt about them, but I never asked.

As time went on, and especially after she died, I began to admire that she had continued to make pots, even though she must have known they were primitive compared to what she used to make. I wondered what made her keep going with pottery; what was she getting from it? How was she able to accept the pots she made, to be content enough with them to keep working?

In talking to older artists, I hear them express the satisfaction of still being able to do their creative work, that the process is more important than the end product.

Artist Rose Abrahamson, who will turn 93 in October, says about her work, “I’m so glad I’m still fooling around. I don’t have to do it for anybody — I can just play with it.” Her paintings and collages fill her house; they’re never really done, and they stimulate her to keep working. As we looked at her new work, returned from a recent show at The Anchors in Edgartown, she says about one collage, “Then I see it’s not nearly good enough and I’ll have to pull it apart and start over. It’s too stagnant. I should get three or four little children in here and have them scribble over it.” Her work is her playground. The process of making art is what gives her joy, and keeps her connected and involved in the world.

As we age, our outer lives seem to constrict as we are forced to give up things, either because we can’t do them anymore or someone else says we shouldn’t. Despite a perfect driving record, at age 91, Abrahamson had to give up driving a car; she still feels that great loss of freedom. But even though she says her recent work has “squeezed the last bit of juice” out of her, her collection of scraps of paper and rusty metal, bits and pieces from old work, and her continuing imagination keep her at the easel. Abrahamson says, “A gift has been given to me in my old age. I can’t stop; I shouldn’t stop.”

In her article “Why the Elderly Are More Creative,” which appeared on the Huffington Post in October 2011, 96-year-old writer Rhoda Curtis wrote, “The nature of the creative process is so basic to all human endeavors that we . . . take it for granted in the same way we take our sense of smell and taste — it is just as basic. We are not only hard-wired for creativity, we are hard-wired for the process, and this does not change as we age — trying something different, something new, requires a process of trying, testing, evaluating, and trying again. It’s fun, and even when we fail, it is the process that is so rewarding.”

More and more of us baby boomers heading into old age are unwilling to accept the status of old person on the sidelines of life. Historically, artists especially have been unwilling to stop doing their art just because of old age and infirmity. Matisse spent his later years painting from his bed or wheelchair; Picasso kept experimenting with different styles of working until he died at age 91. Some curators think the pieces Willem de Kooning painted in his last decade, as he came under the influence of what was probably Alzheimer’s disease, were his best work. Perhaps knowing his time was limited, de Kooning decided to be less self-critical, and produced voluminously.

Essayist and novelist Edward “Ted” Hoagland, 81, is completing his fourth book in four years. About writing at this time in his life, he says, “If you have the work habits of 63 years, you’re more relaxed. I’m not tense about the process or project, not as competitive.”

Chilmark dancer, writer, and rug hooker Sandy Broyard believes that age can endow you with a type of freedom people often don’t have when life is crammed with jobs and raising kids. As with making rugs, she says, it’s safe to take risks because things can be undone. Sandy, age 76, dances four or five times a week, mostly with the improvisation group What’s Written Within, which she co-directs with Sally Cohn, age 70. The group comprises dancers and non-dancers ages 17 to 87, and performs at The Yard and elsewhere on the Island. Sandy has danced most of her life, and says, “Being a dancer, I have a pretty clear connection to dance experiences from when I was a child through all the different parts of my life. When you have an art that you stick with, you don’t lose the memories, the connectedness of it. It just becomes fuller.”

Art connects us to our past, and can expand our emotional interiors at a time when our outer lives, and even our bodies, are shrinking. Interaction with the arts, both as viewer and listener or as someone involved in its creation, is stimulating, and brings us more into connection with the world and ourselves.

For more than fifty years, art has nourished Rose Abrahamson. A few years ago, she wrote that art “is an important release for the vastness of my imagination and also a never-ending learning adventure.” The studio, she said, “is the only place in my life where I am the captain of my ship and can explore uncharted waters, with no rules to follow and no promises to keep.”

Leave a reply